‘Obiter Dicta’ is the legal term for a Judge’s Comments, so it seems a good title for my Bloggy Bits. My posts are on various different subjects and the following emblems will help identify the sort of thing that I’m going to be going on about in any particular post:-

The ‘STORIES’ referred to are the true but inconsequential anecdotes that I’ve been boring people with years. So why should you escape?

24 Feb.2020

DID I TELL YOU THE ONE ABOUT ME AND MARC BOLAN

Well that’s pushing it a bit, but I did come across the Elfin One on three occasions. On the first of these, the original ‘Van der Graaf Generator’, consisting of Peter Hammill and myself, supported the original ‘Tyrannosaurus Rex’, consisting of Marc Bolan and Steve Peregrin Took, at The Magic Village club in Manchester in 1967. There were superficial similarities between the two outfits, since both were duos, each consisting of a gorgeous, guitar strumming singer with an odd-ball side-kick bongo-wielding/backing vocalist.

Peter and I were pretty left-field, doing songs later to be heard on ‘Aerosol Grey Machine’ and ‘Fool’s Mate’, with me bashing away as best I could on bongos and ocarina, and occasionally using a typewriter as a percussion instrument. However Marc’s band was truly weird, due mainly to his bizarre, high-pitched warbling vocals. He was certainly a very compelling performer, but we didn’t enjoy any back-stage hippie camaraderie. He clearly regarded us as pond-life, and having somehow copied his two-man format.

Come to think of it, we got up the noses of some other bands we supported, including ‘The Third Ear Band’, an almost spookily priest-like and po-faced instrumental ensemble, who accused us of ‘ruining the vibes, man,’ with our essentially jolly set of songs before they went on. It occurs to me that this was probably the last time anyone ever accused Peter’s music of lacking seriousness.

A few months later when Peter and myself had decamped to London, at that time at its most Swinging-est, Peter somehow got hold of John Peel’s address, which was quite a coup. At the time, Peely was the absolute epicentre of ‘progressive’ music, and as a radio DJ and Melody Maker columnist had enormous influence on the scene. Accordingly we went, unannounced, and complete with guitar and bongos, to JP’s muse cottage in central London, and knocked on the door. The DJ stuck his head out of a first story window to see who it was and we called up, “We are ‘Van der Graaf Generator’, can we play you some songs?” “Come in Van der Graaf Generator”, he replied.

Peel was a delight, hospitable and appreciative. We sat on his floor and did a few songs, quite which ones I don’t remember, but as soon as we got started, a door opened, and in came Marc Bolan, his tiny naked figure swathed in a bath towel. He glared at us in a distinctly hostile manner and stalked across the room to exit by another door. JP said nothing and we continued our ‘audition’, which resulted in a nice mention in his ‘Perfumed Garden’ column in the Melody Maker, which did us no harm at all.

In the late ‘60s, ‘Seed’, the Macrobiotic Restaurant in Westbourne Terrace, near Paddington Station was a delightful place to eat, and though I was a thoroughgoing carnivore at the time, I thought their vegan food was delicious. In my last sighting of ‘the Bopping Elf’, as the press was then calling him, I was eating there alone when a large central table was suddenly filled with by Bolan and his entourage; seven or eight ‘beautiful people’ dressed in the height of expensive hippie fashion with multicoloured psychedelic togs, perhaps from the Beatles’ ‘Apple Store’ or ‘Granny Takes a Trip’. Enthroned at the head of the table sat Bolan, going the full ‘Hobbit’, with hair flowing about his shoulders, draped in a velvet cloak and wearing a child’s, silver plastic armour breast-plate. This should have looked completely ridiculous….. but he looked absolutely fabulous!

11 February 2020

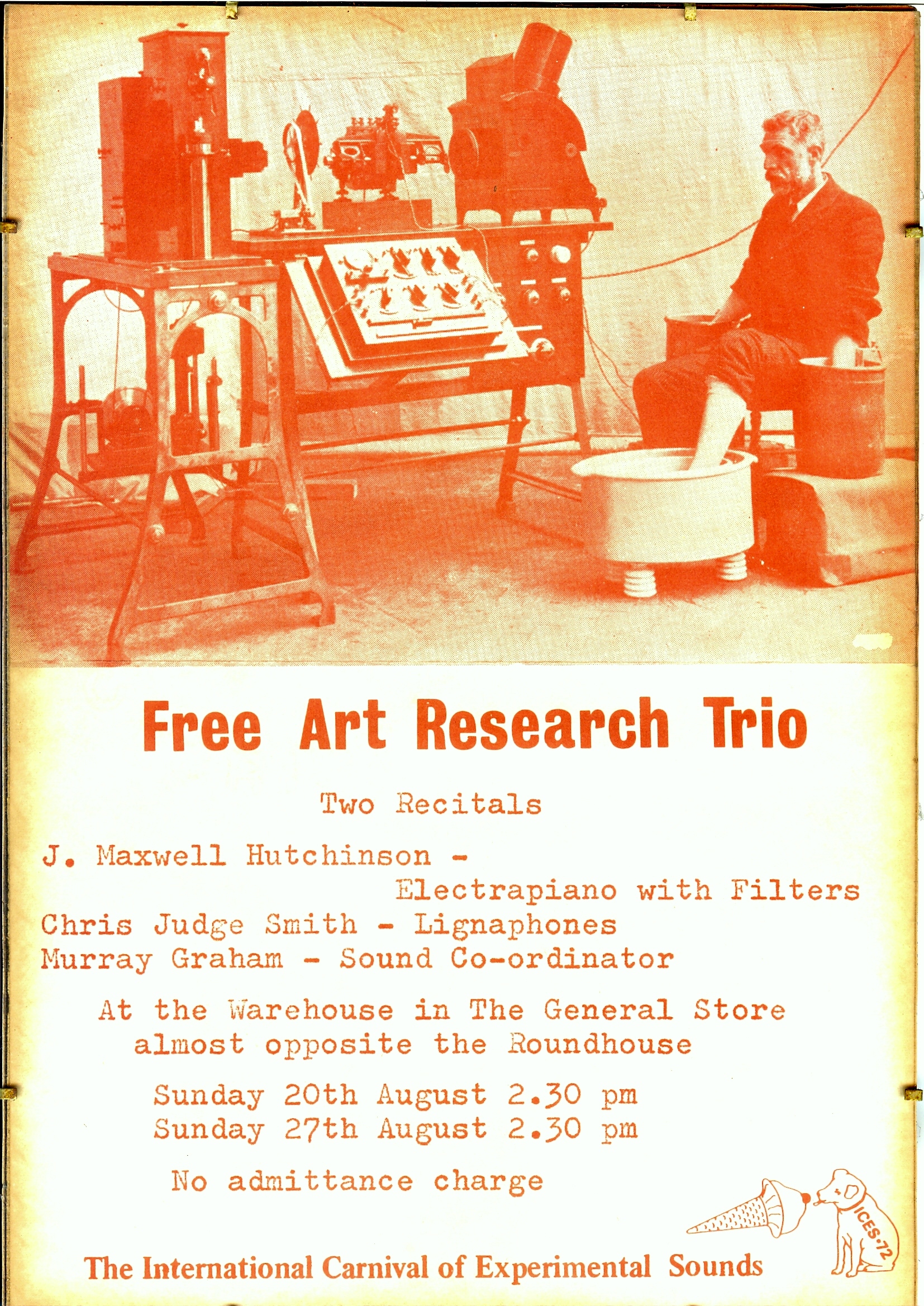

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 1

I want to tell you about a strange corner of my musical life that is not represented to any great extent on this website, and not at all in any recorded musical form. This story is half way between a musical essay and one of my after-dinner tales, and it’s quite long, so I will write it in four parts.

Max Hutchinson and I worked on theatre musicals together between around 1975 and 1981 (as can be explored in the Archive section of this site.) However we also had other joint musical interests, including a sort of post-punk Beat Group called ‘The Modern Beats’ (see my Gallery for 1980) and also a fascination with ‘Free Music’, the name improvised, avant-garde sound performances were called at that time. We were, however, not so much interested in listening to this stuff as performing it (far more fun, we thought) and we determined to form an ensemble of some kind to inflict free-form musical anarchy on the world.

A nice young couple we knew had a spare room which they allowed us to use as our laboratory, and over a period of months, we started to develop a performance protocol. Because of our involvement in rock’n’roll, we were enthusiastic about multi-track recording, and we eventually devised a method of producing multi-tracked noise-music in real time. In today’s age of laptops and looping pedals, this seems a simple ambition, but at the end of the 1970s, it was a pretty far-out proposition.

But first we had to decide on what instruments we would play. Maxwell owned an ancient Hofner Electra Piano, currently described on a period instrument site as ‘one of the rarest and best-sounding tine/reed electric pianos ever made.’ Max removed it from its wooden casing, so that its mechanical guts were fully exposed, and fed its sound through a collection of fuzz-boxes and wa-wa pedals, producing a surprisingly wide variety of strange, alien tones. As for me, it was decided that I would play a percussion kit entirely made up of wooden instruments of one kind or another. I made a bass-drum out of a tea-chest, and a series of drums consisting of long, square-section, wooden tubes with balsa wood ‘skins’. I also had a collection of children’s xylophones, Asian wood-blocks, and a group of wooden rulers mounted on a box that could be twanged, the way kids did on their desks in the class-room. There was also a baulk of timber and a saw. Each of these wooden elements were mic’ed-up with World-War II RAF contact throat-microphones, bought from the legendary Laurence Corner surplus shop north of Tottenham Court Road. (All this experimentation was, as you would guess, done very much on the cheap) and we described this collection of wooden junk as ‘Lignaphones’.

The sounds from my throat-microphones and the mangled output from Max’s keyboard were fed into an ancient Vortexion valve amplifier to be blasted through a single loudspeaker, and also sent to an old reel-to-reel tape recorder. This was fitted with a rather cunning tape-loop cassette containing three-minutes of quarter-inch magnetic tape. We would improvise for three minutes, at which point the tape loop would automatically start to play back through the loudspeaker, whereupon Max and I would play along with what had been recorded, adding another layer of ‘music’. This next layer was recorded onto a second elderly tape recorder fitted with another three-minute tape loop, and when this was full of our noises, both cassettes played back, while Max and I merrily added a third layer of live mayhem on top. All our numbers were therefore exactly nine minutes long, and it made a splendid racket.

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 2

As the name suggests, our band required a third member. This was our friend Murray Graham, who was the onstage technician who manipulated this collection of antique technology in real time. The amp, speaker and tape recorders were mounted in a Dexion framed construction proudly named the Tower of Power, while the stage set-up with our bizarre looking instruments and festoons of wiring looked like nothing less than the set of a cheap ‘mad professor’ science fiction movie. Thus came our name, and thus developed our stage personas as white coated, clip-board wielding, fake scientists. The acronym of our name was, of course, FART.

We did a few gigs, and audiences enjoyed our essentially light-hearted and self-mocking take on ‘free music’. Any hostility came from other members of the avant-garde music scene. This was understandable; for while Maxwell was a really excellent rock guitarist and a tolerable keyboard player, he was no jazz musician, while I was a vocalist and my capabilities as a percussionist were more or less exactly zero. We both worshiped jazz in all its forms, but the real musicians on this scene were, without exception, virtuoso jazz soloists who had simply moved beyond the confines of conventional musical forms. They weren’t having a lark with this, they were as serious as cancer, with the possible exception of saxophonist Lox Coxhill, a hero of ours, who seemed to enjoy absurdity. We took our ‘funny noises’ seriously, and strove to do our stuff as well as possible, but we had no credibility whatsoever as genuine ‘free music’ practitioners.

However, Maxwell was an entrepreneurial live-wire, and managed to organise paying gigs at which the doyens of the avant-garde scene, who had limited opportunities to perform in public, found themselves playing on the same bill as these young clowns. Maxwell would adopt a plummy-voiced, pompous manner (perilously easy in his case) to announce the pseudo-scientific titles of each of our nine-minute numbers (I remember ’Benzine Rings’ and ‘Kundt’s Tubes’) and off we would go. Talk about the confidence of youth.

16.02.2020

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 3

I cannot remember the circumstances, but in the Summer of 1972 we were introduced to the extraordinary Harvey Matusow who, with his wife Annea Lockwood, were at the very centre of London Counter Culture. An ex-pat American, Harvey was an author, musician, entrepreneur, political miscreant and showman. This is not the place for even a short resume of his bizarre career, but I can thoroughly recommend Dave Thompson’s book ‘The Avant-garde Woodstock’ for a full exploration of what Harvey was about to unleash.

We were invited to visit Harvey at his home in Ingatestone, Essex, where Annea Lockwood had planted their garden with a series of half-buried pianos. He was, he told us, in the final stages of organising a massive, two-week festival of avant-garde music to be based at the Roundhouse in Camden, and to be called the International Carnival of Experimental Sound 1972, otherwise known as ICES. The ebullient and charismatic Harvey invited us to take part, and we naturally jumped at the chance. We wouldn’t be paid, but would get free passes to all events. The only drawback was that the Festival was to due start in a couple of weeks, and the program had already gone to the printers, so we would need to publicise our own shows. However, Harvey agreed that we could make an on-stage announcement after one of the major Roundhouse concerts.

We thought that we had better take the opportunity to make a bit of a splash with our announcement, so we made another visit to the invaluable Laurence Corner and hired an impressive silver space suit, complete with helmet. Our plan was that Max and I would come on stage, me in my space suit brandishing a loudly ticking Geiger counter with which I would sweep the audience, while Maxwell in his white-coated mad scientist persona would announce our forthcoming shows and explain that our music was mildly radioactive and needed to be tested as a precaution.

However, on the designated day, it appears that Harvey had omitted to tell stage management that FART were due to make an announcement after the evening show. On the other hand, we had also omitted to tell Harvey about the ‘art action’ we were planning. I forget which performance it was that we had been told we could come on after, but as we waited in the wings, I was hot and disoriented, finding it difficult to breathe in my steamed-up goldfish-bowl helmet.

As soon as the applause had died down and the musicians, whoever they were, had departed, Max guided me onto the massive Roundhouse stage and I began my Geiger counter nonsense. However, Max had barely started to announce our gigs before we were both jumped on by two burly security men, who, seeing what they perceived as an unauthorised stage invasion, seized us and dragged us bodily from the platform. Cocooned uncomfortably in my cumbersome costume, I had no idea what was going on, but I could hear Maxwell protesting loudly as we were forcibly ejected through a rear door of the building.

The Roundhouse was built in the Victorian age as a repair shop for steam locomotives and was, at the time, still surrounded to the rear by derelict railway sidings. We stumbled around wretchedly in the dark for some considerable time until we found a fence we could climb over into the relative normality of Chalk Farm Road.

Our gigs themselves went well and were held at ‘The Warehouse at The General Store’, a spacious venue directly opposite the Roundhouse. Prior to this, Max and I stood outside the main venue for hours leafleting those leaving the concerts with details of our own shows, which ended up being quite well attended. I remember giving a flyer to John Cage, but I don’t think he turned up.

We also took full advantage of our ICES free passes and saw a lot of strange and inspiring acts. On one occasion I found myself seated next to a young guy who was bopping about in his seat, apparently really digging the honks and squeaks going on onstage.

“Hey, you really like this, don’t you”, I said.

“Yeah, it’s far out.” His voice was a bit slurred, and I assumed he was stoned, like the majority of the audience.

“It’s even more fun to do it”, I said.

“Wish I could, man.”

“Well I’m going to be performing tomorrow, and I can’t play a note.”

“’Fraid I couldn’t though.”

“Why not?”

“I’ve got Cerebral Palsy…”

19.02.20

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 4

Our most memorable gig came through contacts with the Jazz Centre Society, based at the time, as I recall, in Covent Garden. An old school-friend of ours, Dr David Mitchell, an accomplished jazz saxophonist, was an active member, and when a benefit gig for the Society was announced to be held at the legendary Ronnie Scott’s Club in Frith Street, Soho. We managed to wangle ourselves onto the bill. At that time Ronnie Scott’s Club had an upstairs venue where lesser bands and rock groups performed, but this gig was to happen downstairs, in the Jazz Club proper.

I cannot exaggerate the thrill of actually playing on the same stage, with its strange, undulating plaster rear wall, on which we had seen so many superhuman Gods of Jazz perform. This was Holy Ground to us, and of course in the normal course of events we would never have got within a million miles of performing there.

For the event, the Trio were augmented by David Mitchell on Saxophone, who as a busy hospital doctor, already had his own white coat. I can’t recall whether he partook of our double-tracking facilities or just blew over the top of our stuff, but in any event, it all went down as well as our other gigs. (One advantage of playing Free Music is that one cannot actually make mistakes as such, as there are no right or wrong notes.) I recall the audience enjoyed me ‘playing’ a length of timber by going at it with a saw, the noise splendidly amplified by our trusty throat-microphones. The evening was one of the musical highlights of my life.

Amazingly, both the three minute tape-loop cassettes still survive from our final gig, but I have never considered playing them, as they would be missing the essential ‘third layer’ of live performance that went on top.

The only photo that survives of the band was taken that night, and can be seen in my Gallery (1972), and here is one of our posters:-

30 January 2020

DID I EVER TELL YOU THE ONE ABOUT ME AND ORSON WELLS?

DID I EVER TELL YOU THE ONE ABOUT ME AND ORSON WELLS?

It was in the early 1970s and I was in Soho, no doubt trying to set-up some ill-starred music project or other, and probably looking like a weekend hippy. It was pouring with rain and I was trying to get a cab to go home…

(This fact alone shows just how long ago this was. In those days I could actually afford to hail a black cab in central London. Only last year, a train cancellation meant that I was forced to take a taxi from London Bridge Station to get to a mixing session I had booked in a recording studio near Chrystal Palace. My fare ended up costing more than the studio session.)

Anyway, back to the early 70s; there were precious few cabs about in Dean Street, and I became aware that someone was standing next to me in the rain, also trying for a cab. Under these circumstances the two rivals for hailing rights ignore each other’s presence (‘Oh, were you there before me? I didn’t know…’) so I cast not so much as a sideways glance at him. I knew it was a ‘him’ as I could hear deep rumbles of discontent at my side.

Then, coming out of a side street, I saw the longed for lit-up orange taxi sign. I waved, he saw me; me, not the other fellow, and pulled over on the opposite side of the street. As I hared over to the cab I heard an explosion of rage behind me. I reached the taxi and risked a look back across the road. My competitor was Orson Wells, looking like someone dressed up as Orson Wells, with huge beard, long black overcoat with astrakhan collar and black homburg hat.

I thought for a moment, opened the cab door and gestured to the great man. He lumbered across the road, as I held the door for him and he climbed in. Not a word was spoken, but he bared his teeth at me in a scary smile, and in his fierce eyes I read the message, ‘I’m Orson Wells, of course I get the cab!’

19th March 2019

OPERA : ‘BEL CANTO’ OR ‘CAN BELT-O’?

The Operatic Voice is not really my cup of tea. The Operatic Voice is generally too much for me; it’s too loud and too dramatic. Opera singers are trained to produce an astonishing volume of sound while still producing a beautiful tone. They are supposed to be heard at the back of a gigantic opera house, without using a mic, and over the racket made by a large orchestra knocking seven bells of hell out of some grand climax, and this requires extraordinary sound-penetrating qualities. An operatic Tenor I knew referred to this piercing quality as ‘the blade’. You had to have ‘the blade’.

The singers who produce this operatic voice are astonishing musicians, awesome vocal athletes and dedicated, sensitive artists, but, to my coarse and uncultured ears, their performances often come over as a lot of shrieking and bellowing. I sympathize with the story of John Gielgud who was directing an opera production and wished to address the cast during a rehearsal. Advancing on the stage while the cast were still at full throttle, and failing to attract their attention, he cried, ‘Oh do stop that dreadful singing!’

I find it much easier to appreciate other aspects of the formally Trained Voice. The ‘Church’ voice is a different animal from the ‘Opera’ voice, I love the quieter, sweeter tones of the singers, both male and female, who generally perform in a liturgical setting, while a soprano or contralto performing wordless music with melismatic pure sound, can be miraculous. Bachianas Brasileiras #5 by Villa Lobos, for example, features a wordless soprano in one of its various arrangements, and is a transcendent experience. In his ‘Sinfonia Antartica’, Vaughan Williams pulls the same stunt with magical results, as does Holst in ‘The Planets’. However, these are women’s voices; your Tenors and Basses, it seems, always have to be singing about something, well they’re men…

An opera is a sung play. Characters, in opera, are supposedly communicating with other characters on the stage, and are also communicating to the audience. They have to sing words, but in the operatic tradition they enunciate them in a very particular and peculiar way so as not to compromise their precious tone.

The comprehensibility of sung opera probably varies depending on the language of the text; some languages have vowels that are more compatible with operatic enunciation than others. Italians can probably understand a lot of what is being sung in Italian, and my guess is that German operatic audiences can also follow most of what’s going on. In English, however things do not work so well.

Many opera singers work admirably hard to make an English libretto as clear as possible, but when a few lines, usually of recitative, can be understood, it often sounds ridiculous because opera singers are trained to pronounce English words in the most exaggeratedly ‘posh’ or aristocratic manner imaginable. I have confessed in an earlier post that I, myself, use a slightly ‘poshed-up’ accent to perform in, because it makes our wonderful, but infuriating, language easier to sing, but Operatic diction in English makes Jacob Rees-Mogg sound common as muck. All the dramatis personae in an opera are sung in this ridiculously toffee-nosed manner, so that working class, or servant characters are sung with the cut-glass accents of members of the House of Lords circa 1850.

Sadly, this emphasis on volume and tone means that Opera sung in English is mostly unintelligible; both to me, and, it seems, to many other people. I put forward, as evidence, that fact that opera productions performed in English, in the UK, frequently have the words projected above the stage as ‘surtitles’.

I should re-state this situation, as it is so bizarre. English-speaking audiences, listening to performers singing in English, need to have the words there in front of them because no one can understand what the performers are singing.

What is wrong with this picture?

For this reason, most operas, are performed in the language in which they were composed. ‘Boris Godunov’ sung in English sounds about as intelligible as ‘Boris Godunov’ sung in Russian so what would be the point of translating it?

An opera fan would protest that it’s all about the music, not the words. Fair enough: but if opera is supposed to be experienced as a piece of Total Art, a Gesamtkunstwerk, it doesn’t help if a significant part of the kunst doesn’t werk properly.

19th March 2019

DID I EVER TELL YOU THE ONE ABOUT ME AND KIRK DOUGLAS?

In 1976 I was in Edinburgh as Musical Director of ‘The Kibbo Kift’, a musical at the Traverse Theatre that I had written with composer Maxwell Hutchinson. (Script and recordings are in the Archive section of this site, by the way.) I was in Princes Street Gardens one afternoon, in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, listening to a pipe band, when it came on to rain. The pipers opened their packs and produced the most wonderful plastic macs I had ever seen. Long, black and silky, they had a cape instead of sleeves, an ‘Ulster’, as might be worn by Sherlock Holmes or a pre-war policeman. As well as looking super-stylish the cape enabled the pipes to be carried and played ‘under cover’.

I had to have one, and approached one piper to inquire where they came from. He asked their Quartermaster, and I was told they could be obtained from McTavishe’s ‘Heeland Ootfitters’. On my next afternoon off I located the small shop and inquired whether they had any piper’s rain capes. I was directed to the basement, which was deserted, and among the racks of clothes found a rail of the garments in question.

I found one in my size, put it on, and was admiring myself in the mirror when, without warning, a voice spoke behind me. It was a deep, resonant and American voice. ‘That’s very Holmsian’, it said. Where had he sprung from? I wondered. I turned round and there was Kirk Douglas. I goggled at him in astonishment, but it was him alright. Really tall with brilliant blue eyes, but not wearing the Valentino suit or expensive leisurewear proper to Hollywood royalty, but dressed in a rough poncho, with a six-day beard, as if he’d materialized from the set of one of his grittier Westerns, ‘Indian Fighter’ maybe, or ‘Last Train from Gun Hill’. The famous dimple on his chin looked absolutely bottomless.

I managed to gabble on a bit about Pipe bands and their rain-wear, and he was very pleasant and chatty. I asked him what he was doing in Edinburgh and he said he was competing in the Pro-Am golf tournament. I told him I had a show on at the Traverse and said I’d leave his name at the door. ‘You don’t have to come’, I said, ‘But it would be fun to leave your name at the door.’ We had a bit of a laugh and I took my cape up to the Ground Floor, leaving Spartacus alone downstairs. As I paid for my purchase, I quietly checked with the proprietor. ‘Downstairs, that is..you know?’. ‘Oh aye,’ he answered conspiratorially, ‘Mr Douglas… he’s buying a kilt!’

18th March 2019

SINGING IN ENGLISH

SINGING IN ENGLISH

Singing in English is not easy, and singing in non-accented, non-regional, middle-of-the-road English is pretty well impossible. It’s to do with the vowels; they’re fine for the talking, but start to sing and they don’t fit in the mouth; you just can’t make them sound good, or put any power behind them. Italians can sing in regular Italian, and the French in normal French (except for their weird habit of adding an extra final syllable to any word ending in ‘e’) but to sing English at all, the singer has to adopt some form of accent. Almost any accent will work fine; Scots, Irish, Welsh, or Cockney can sound great, particularly for singers who talk like that as well (although this does not necessarily have to be the case. That great vocal stylist Bryan Ferry speaks without much of a North-eastern accent, but sings in broad Geordie). However, for singing Brits who don’t have some regional or ethnic identity to bring forward, the usual fall-back position is to adopt some form of American accent. American vowels are super-easy to sing, and though any actual American can spot the imitations a mile off, the majority of non-classical British vocalists subside into one of a weird variety of phony Yankee pronunciations. This normally has nothing to do with them wanting to sound like Elvis or Lou Reed, it’s a matter of acoustic necessity.

I have struggled with this problem myself. To me, my speaking voice sounds completely neutral, but other people hear definite Public School cadences. My parents, both from working-class Woolwich, and not the slightest bit snobbish, nonetheless deliberately lost their ‘common’ accents to ‘get on in the world’. They insisted that I did the same, and, in my teens, would often tick me off for coming-out with any of those Estuary inflections that became so fashionable in the Sixties.

My solution to the singing-in-English problem was to develop my natural accent into a sort of old-fashioned ‘posh’ voice to sing with, and I fixed on this quite early in my soi-disant ‘career’. It continues to work well for me, from the technical, acoustic point of view, to the extent that at least people can hear what I’m singing about. Thus it was, that from my late teenage years, I came to think of myself as singing in the character of some frightful, elderly clubland bore making his dreadful jokes in the Lounge Bar, and now, half a century later, God forgive me, I am that man, or something uncomfortably like him.

This vocal persona, also fits well with the fascination I have always had with the slang, the popular idioms, catch-phrases and demotic patterns of speech of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries; ways with words that have made our language incredibly rich, diverse and flexible. My anachronistic vocal avatar can sing about something being ‘top-hole’, or ‘pisspoor’, or ‘meshugge’, or ‘the bee’s knees’, or ‘fuckin-A’, or ‘peachy-keen’, or ‘downright dis-servicable’ and sound as if he means it.

18th March 2019

TUK-TUK

TUK-TUK

Travel in India is best accomplished, if the distances involved are not too great, by the three-wheel motorised rickshaw known as the tuk-tuk. They have a windscreen, a roof and a back, but no sides, and, as a passenger, the sights, sounds and smells of this wonderful place are up-close and personal. You are a participant, an authentic part of the spectacle of the street.

Indian drivers are bold, daring and assertive. They drive with élan and panache, slicing in front of each other with aggressive precision. (The Indian driver is highly skilled – or dead). The Indian words for ‘cutting people up’ on the road is probably just ‘driving’. The Indian driver, both male and female, sounds his or her horn continually. ‘Here I am!’, it announces. ‘Look out, I’m coming through!’ or just ‘Woopee!’ Yet all this apparently ruthless roadhoggery causes no anger or resentment. The mad traffic rushes onwards in an overwhelming atmosphere of tolerance and forbearance. We have always felt quite safe on Indian roads; the Shiva or Ganesha or Shirdi Sai Baba on the dashboard will see to that.

Tuk-tuk drivers are street-smart to an extraordinary degree, they know every inch of their town or city from boulevard to dank alleyway and, once you know where you’re going, and what the fare ought to be, you can get twenty minutes of fast, fascinating transportation for around £1.50.

The drivers come in all varieties, including plausible rogues who are extremely keen that you visit their ‘uncle’s’ emporium, or gentle, barefoot philosophers. Some drivers have excellent English and are as good as any professional guide. A recent week in Mysore was made memorable by one such paragon who organised our sightseeing with effortless professionalism. (Our thanks to Mr Lokesha, and his ‘Green City Ride’).

Over the years Fiona and I have had some remarkable tuk-tuk experiences. In Jaipur we were latched onto by a flamboyant young chancer whose routes around the city in ‘the fastest rickshaw in town’ were curiously punctuated by brief, unscheduled stops; at a chai stall, or a street corner where our driver would scurry from his cab to hold brief mysterious meetings. When the tuk-tuk developed engine problems, he opened the fuel tank and, fishing around inside, withdrew a package wrapped in plastic, whereupon the engine was restored to life. It was only at this point did we realise that we were providing excellent cover for his drug delivery round.

At a seaside resort on the West coast another young driver, who had taken us to-and-fro a couple of times before, picked us up one night and immediately headed in the opposite direction from the way we wanted to go. ‘Doon be crass! Doon be crass!’ he wailed. ‘You are my Mother and Father!’ We were contemplating our apparent kidnapping with some misgivings when he swerved off the road and onto the beach where crowds had gathered in the darkness for a religious festival.

Three huge temple elephants in golden armour stood guard as, lit by burning torches, Brahmin priests in loincloths repeatedly poured butter-ghee, milk and who-knows-what-else over figures of the Gods, which were then picked-up and rushed into the sea to be washed in the breakers before being returned for more anointing. Our driver was very pleased with himself as we took our darshan, and also, we realised, completely off-his-face on bhang or something similar.

On our recent trip to Madurai, we hailed a rickshaw to return to the hotel from one of the city’s many rooftop restaurants. He was already waiting for someone, but another driver he was talking to seemed eager to oblige. He was a tiny old man who waved his hands in the air and cackled at us maniacally, revealing a startling lack of teeth. We climbed aboard his rickshaw rather apprehensively, he revved his engine, and took off like a rocket. Tuk-tuks in Madurai are fueled with LPG but this one must have had nitro dragster fuel in the tank. Hunched over the handlebars, cackling loudly and occasionally waving one hand in the air, he drove at enormous speed, overtaking everything and frequently on the wrong side of the road. At times we must have been going at 70mph, when Indian traffic seldom exceeds 50mph. White knuckled, we reached our destination in exactly half the time it usually took, and the old man cackled happily over his £2.00 fare.

In all but the greatest Indian cities, cars do not predominate. The street is owned by the two and three-wheelers. In the evening, when everyone is on the move, thousands of motorbikes, scooters and tuk-tuks dance and weave around the crowded, oversized buses which are gashed, seamed and welded like something out of Mad Max. Motor rickshaws, licensed to carry two passengers plus driver, might have a dozen or more people crammed inside. Cows, wandering free and unconcerned amid the heaviest traffic, must be negotiated, and there is a sprinkling of sturdy sit-up-and-beg bicycles (which all feature eminently sensible rear-wheel stands that leave the bike firmly upright rather than balancing on a little spike).

Women and girls ride powerful scooters, and are as dashing and daring drivers as the men, who mostly ride motorbikes, including gleaming and magnificently retro Royal Enfields. So many bikes; with two-up, three-up, four-up; whole families out for the evening on the family Kawasaki, mother in jeweled sari, sitting side-saddle at the rear, the fluttering skirts of the sari perilously close to the rear wheels, then maybe eldest daughter; mother and daughter’s blue-black hair in ‘french braids’ entwined with coils of Jasmine, floating in the wind, then comes proud father, his hair styled in an immaculate quiff, then youngest son standing at the front grasping the handlebars. Helmets? Who would want to wear something so hot and uncomfortable and crushing of the hairdo?

And this whole river of blazing lights, incredible cacophony of noise, and overwhelming engine fumes is hurtling onward into the warm, soft, black-velvet Indian night, and the sound rises and echoes amid the colossal towers of the temples and becomes one great metallic, resonant ‘OM’.