A GIFT FROM THE GODS

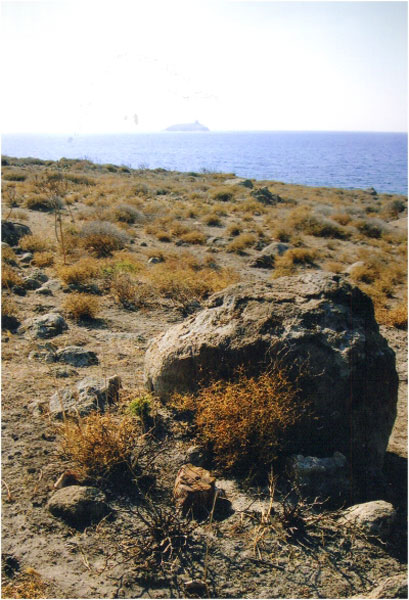

On the volcanic North-East coast of the island of Lesvos, a remote, sun-baked promontory juts into the Aegean. At its foot is a glittering, agate-studded beach, maybe a quarter of a mile long, which usually remains completely deserted, even at the height of the holiday season.

In August 2006, I was walking on this headland among the lava flows and thorny scrub. Crimson grasshoppers jumped about excitedly, but the scorpions thankfully didn’t; preferring to lurk beneath their ancestral stones. I was dressed for comfort in les espadrilles, and le Panama de monsieur, but apart from these, I wore nothing but a smile, since there was no living soul in sight, except Fiona, my girlfriend, basking on the beach below, where a kite, flying in the permanent breeze, marked the location of our little encampment.I wandered to and fro looking at fossilized trees whose stone trunks, some composed of solid agate, emerged vertically from the ground where they had once stood as living trees, 20 million years ago. In this primordial and archaic landscape, it suddenly seemed quite probable to me that Pan or maybe Dionysus, perhaps with a few Dryads in tow, would appear over the rise. It certainly felt as if someone, or something, was approaching.

What happened instead was that I ‘got’ a song. Within the space of a few minutes, a killer riff, a strange and compelling chorus melody, and a set of decidedly odd lyrics had arrived in my head; unplanned, un-worked-for and totally unexpected.

INSPIRATION v. PERSPIRATION

Like many, much better, songwriters, and far, far greater composers, I have long been conscious of the weird phenomenon of Artistic Inspiration, and I have been its beneficiary on more occasions than I really deserve.

Inspiration is a spooky thing. How it works is a real puzzle, and where it actually comes from is anybody’s guess. The traditional view, which held sway from ancient times until the Enlightenment, was that Inspiration (literally meaning ‘filling with breath’) came from external Higher Forces of some kind; the Gods, the Muses, the Spirits, or something in that line. In modern times, an ‘internal’, psychological, explanation has been favoured, in which some part of the subconscious mind of the artist spontaneously generates music, or words, or images.

Either way it’s damn good stuff. You get much better material than you could come up with by your own hard creative work, and there is no effort involved. If you are a creator of music, then new, original music just appears in your head, as if by magic. It can sometimes be very different to your normal music, the stuff you write yourself, and this can help change your artistic direction. And it’s free; what more could you want?

On the other hand, It’s completely unpredictable and uncontrollable. You might get several fragments of terrific music in the space of a week (often appearing at the most inconvenient moments), and then Inspiration can vanish, for months or even years at a time.

Inspiration is also dangerously fragile. It seems to be part of the same universe that dreams come from, and, like dreams, Inspired material can slip from the mind in an extraordinary way. You can wake from a vivid and remarkable dream, and yet in a minute or so it has completely vanished from your memory. In the same way, you can ‘get’ a splendid tune projected into your head, a highly memorable melody, and yet it too has vanished without trace by the time you get round to noting it down.

At the start of my career, I lost a couple of fantastic songs (or potential songs) in this way. "That’s so brilliant, I could never forget it", I said to myself. "And I’ll have time to put it on tape tomorrow." But could I remember it the next day? Could I hell!

Because I soon realised that I would need all the help I could get to become even a half-way decent songwriter, I soon developed the habit of recording my ‘hums’ onto a little micro-cassette recorder, right away, as soon as I got them. If I didn’t have this device with me when Inspiration struck, it could result in rather eccentric behaviour on my part. I have lost count of the number of times I have stood in a public phone box, singing away down the phone to my home answering machine, while passers-by gave me a wide berth.

At one point, as a much younger man, I used to ‘get’ around one tune or riff every week. Nowadays the miracle happens only a few times a year. However, I now have over three hundred of these ‘hums’. Many have been used on songs and Songstories over the years, but there are still enough left to keep me busy into my dotage, even if I never get another bit of Inspiration, or I lose whatever skills I’ve developed at writing my ‘own’ stuff; stuff I’ve made-up by my own efforts, without the benefit of this Inspiration nonsense.

Most of these bits of Inspirational Fairy Dust consist of a little riff, or a part of a tune, or two or three chords, which I have to fashion into completed songs by the sweat of my brow; so for me to receive a virtually complete song; words, music, arrangement, the works, in one chunk, was extraordinary. I picked my way down through the dunes, humming compulsively, and excitedly announced to Fiona that I’d caught a big fish.

However, I had no way of making a permanent record of the thing; no mobile phone with me to leave a singing voicemail for myself, and I’ve never learned enough music to be able to write things down in musical notation, so I just hummed away to myself for the rest of the afternoon, until the sun sank into the sea behind the mysterious Isle of Silence, and we returned to our little village, where I could get my hands on a cassette recorder. I wasn’t going to let this one get away.

A DAY TO CATCH IT, A YEAR TO COOK IT

My big fish was I Am The Light of the World, and I was surprised and delighted to be given it, but I got quite freaked-out when the same thing happened, in the same place, the next day! This second song, I Don’t Know What I’m Doing, wasn't quite so complete; there was one bit of the tune that I had to write myself later, and I only came home that night with half the lyrics, but the two songs were certainly intended to be part of a single package.

Both featured spoken verses and sung choruses, something I’ve hardly ever done before, and neither featured a ‘bridge’ or ‘middle-8’ to vary the verse / chorus pattern. In my head, they both had similar sounds; the speaking voice was undoubtedly American, there was a screaming saxophone trading bars with a hard rock guitar, there were elaborately multi-tracked vocal choruses, and cellos all over the place.

There were other projects ahead of these songs in the queue, and it would take exactly one year (perhaps to the very day, our holiday diary is never precise on dates) for the two songs to be finally recorded, mixed and mastered. It was obvious that they had to be released, and that I ought to get on with it. I had an unpleasant fantasy of going back to our Greek island the following year and finding an angry Pan or Dionysus waiting for me on the headland.

Greek God:- “So, Meester, you don like our songs what we geeve you?…”

Judge:- “No, they’re fantastic. I’m very grateful. Er… thank you very much.”

Greek God:- “Well, you say you like, but is one year gone now, an you don do nothing with thees good songs, so fuck you, we don give you no more…”

LET’S START A BAND

I started work on the backing tracks around March 2007. The songs didn’t sound much like part of any Judge solo thing (I would only be singing for part of the time, and there were lots of instrumental breaks) and I was also absolutely certain that I wasn’t about to come up with any other songs of that same special type. So it was that the idea for The Tribal Elders came about; I would record both songs as a two-song single, with my mates, and we would release it as a band. With the possible exception of one band member (and how old is he? No one knows) we all qualify for the title of Tribal Elders, and the name has a nice air of grizzled authority about it.

I wanted to recreate the sounds I had heard in my head on our Greek island, and once I got going, things fell into place with surprising ease. Finding a really exciting lead guitarist for the project was a no-brainer; John ‘Fury’ Ellis was clearly the man. He came down to Studio Judex for the day and laid down an album’s worth of happenin’ licks and extraordinary solos, all over my backing tracks, for me to chose from.

For the saxophones, which played such a prominent part in the imaginary sound-world of the songs, my first choice was equally simple. The bizarre and regrettable events of 2005, within the strange world of Van der Graaf Generator, meant that, since then, David Jackson had been more at liberty to take part in other projects. I have known and played with David since 1969, before he joined Van der Graaf. A man and musician of enormous integrity, I have felt privileged to know him for those 38 years, and we had recently worked together on perhaps the most ambitious of his signature works for children, Twinkle. David is constantly in demand as a performer, animateur, and world authority on music therapy for disabled children, and he is frequently on tour. However, he managed to find a window in his schedule, and Studio Judex resounded with the unmistakable, terrifying blasts of the Double Horn. The studio air-conditioning promptly died from the shock, but despite soaring temperatures, Jaxon gave me everything the songs could possibly need, including a rising sax figure, in octaves, over the final, repeated choruses of I Am The Light Of The World, which finally reaches such a stratospheric altitude that it sounds as if Jaxon, the saxophones, and the song, are all about to explode.

Elder John and Elder Michael at a cafe in North London. Judging by their expressions, elder Judge has just made a typically generous proposal about the division of royalties.

I Don’t Know What I’m Doing also needed an acoustic rhythm guitar track, and for this I called on Brighton multi-instrumentalist and producer Rikki Patten, who works extensively with the legendary Arthur Brown. Playing really good, hard-rocking, rhythm guitar on an acoustic, is a remarkably rare gift, but Rikki can do it, and did it for me for a fried-egg sandwich.

MAKE EVERYTHING LOUDER THAN EVERYTHING ELSE

Recording music is one thing, but mixing it is quite another, and for The Tribal Elders project, I followed my usual plan of recording in my own Studio Judex, but then going to a grown-up professional studio to mix it, with someone who really knows what they’re doing.

John Ellis's musical career began as a punk guitarist. He was a founder member of iconic punk band The Vibrators in 1974 (leaving them in 1979). His friend, the band’s bass player, Pat Collier, went on to become a successful producer, specialising in rock bands, including Jesus And Mary Chain, Primal Scream, The Oyster Band (one of my personal favourites) and Maximo Park. John and I both agreed that The Tribal Elders’ music was rock, by any definition of the word; no unplugged chansonery here, so Pat’s Perry Vale Studios was booked for the job.

The studio is a most impressive establishment, and Pat an easygoing and confident host. He rapidly created mixes that started showing impressive cojones, and in less than a day, we had a couple of masters that were big, beefy, buffed-up (and a little bizarre); Judgemusic on steroids.It only remained for me to organise the packaging and the artwork, and I thought I’d try my hand at the art myself, for once. My limited computer graphics skills meant that scissors and paste and paper played an important part in the process, but I’m still pretty happy with the result.

The discs arrived from the factory just in time for me to take some to Italy for the Lecco Festival in September 2007, where I performed as 'The Major' (complete with military mess dress uniform) in a performance of David Jackson's The House That Cried. (See the News Archive).

It had been arranged for a volunteer to sell the single in the theatre foyer, but this was apparently vetoed by the theatre as being strictly against regulations. No one had told me about this however, and still determined to make our first sales, I rushed from stage to foyer as soon as the curtain came down, still partially in costume and soaked in perspiration, carrying a box of CDs and waving a placard about, advertising The Tribal Elders in Italian. I managed to sell around 45 copies, and the elegant theatre staff took one look at this sweaty lunatic, and decided not to intervene.

A wise move on their part; you don’t mess with Tribal Elders.