11 February 2020

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 1

I want to tell you about a strange corner of my musical life that is not represented to any great extent on this website, and not at all in any recorded musical form. This story is half way between a musical essay and one of my after-dinner tales, and it’s quite long, so I will write it in four parts.

Max Hutchinson and I worked on theatre musicals together between around 1975 and 1981 (as can be explored in the Archive section of this site.) However we also had other joint musical interests, including a sort of post-punk Beat Group called ‘The Modern Beats’ (see my Gallery for 1980) and also a fascination with ‘Free Music’, the name improvised, avant-garde sound performances were called at that time. We were, however, not so much interested in listening to this stuff as performing it (far more fun, we thought) and we determined to form an ensemble of some kind to inflict free-form musical anarchy on the world.

A nice young couple we knew had a spare room which they allowed us to use as our laboratory, and over a period of months, we started to develop a performance protocol. Because of our involvement in rock’n’roll, we were enthusiastic about multi-track recording, and we eventually devised a method of producing multi-tracked noise-music in real time. In today’s age of laptops and looping pedals, this seems a simple ambition, but at the end of the 1970s, it was a pretty far-out proposition.

But first we had to decide on what instruments we would play. Maxwell owned an ancient Hofner Electra Piano, currently described on a period instrument site as ‘one of the rarest and best-sounding tine/reed electric pianos ever made.’ Max removed it from its wooden casing, so that its mechanical guts were fully exposed, and fed its sound through a collection of fuzz-boxes and wa-wa pedals, producing a surprisingly wide variety of strange, alien tones. As for me, it was decided that I would play a percussion kit entirely made up of wooden instruments of one kind or another. I made a bass-drum out of a tea-chest, and a series of drums consisting of long, square-section, wooden tubes with balsa wood ‘skins’. I also had a collection of children’s xylophones, Asian wood-blocks, and a group of wooden rulers mounted on a box that could be twanged, the way kids did on their desks in the class-room. There was also a baulk of timber and a saw. Each of these wooden elements were mic’ed-up with World-War II RAF contact throat-microphones, bought from the legendary Laurence Corner surplus shop north of Tottenham Court Road. (All this experimentation was, as you would guess, done very much on the cheap) and we described this collection of wooden junk as ‘Lignaphones’.

The sounds from my throat-microphones and the mangled output from Max’s keyboard were fed into an ancient Vortexion valve amplifier to be blasted through a single loudspeaker, and also sent to an old reel-to-reel tape recorder. This was fitted with a rather cunning tape-loop cassette containing three-minutes of quarter-inch magnetic tape. We would improvise for three minutes, at which point the tape loop would automatically start to play back through the loudspeaker, whereupon Max and I would play along with what had been recorded, adding another layer of ‘music’. This next layer was recorded onto a second elderly tape recorder fitted with another three-minute tape loop, and when this was full of our noises, both cassettes played back, while Max and I merrily added a third layer of live mayhem on top. All our numbers were therefore exactly nine minutes long, and it made a splendid racket.

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 2

As the name suggests, our band required a third member. This was our friend Murray Graham, who was the onstage technician who manipulated this collection of antique technology in real time. The amp, speaker and tape recorders were mounted in a Dexion framed construction proudly named the Tower of Power, while the stage set-up with our bizarre looking instruments and festoons of wiring looked like nothing less than the set of a cheap ‘mad professor’ science fiction movie. Thus came our name, and thus developed our stage personas as white coated, clip-board wielding, fake scientists. The acronym of our name was, of course, FART.

We did a few gigs, and audiences enjoyed our essentially light-hearted and self-mocking take on ‘free music’. Any hostility came from other members of the avant-garde music scene. This was understandable; for while Maxwell was a really excellent rock guitarist and a tolerable keyboard player, he was no jazz musician, while I was a vocalist and my capabilities as a percussionist were more or less exactly zero. We both worshiped jazz in all its forms, but the real musicians on this scene were, without exception, virtuoso jazz soloists who had simply moved beyond the confines of conventional musical forms. They weren’t having a lark with this, they were as serious as cancer, with the possible exception of saxophonist Lox Coxhill, a hero of ours, who seemed to enjoy absurdity. We took our ‘funny noises’ seriously, and strove to do our stuff as well as possible, but we had no credibility whatsoever as genuine ‘free music’ practitioners.

However, Maxwell was an entrepreneurial live-wire, and managed to organise paying gigs at which the doyens of the avant-garde scene, who had limited opportunities to perform in public, found themselves playing on the same bill as these young clowns. Maxwell would adopt a plummy-voiced, pompous manner (perilously easy in his case) to announce the pseudo-scientific titles of each of our nine-minute numbers (I remember ’Benzine Rings’ and ‘Kundt’s Tubes’) and off we would go. Talk about the confidence of youth.

16.02.2020

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 3

I cannot remember the circumstances, but in the Summer of 1972 we were introduced to the extraordinary Harvey Matusow who, with his wife Annea Lockwood, were at the very centre of London Counter Culture. An ex-pat American, Harvey was an author, musician, entrepreneur, political miscreant and showman. This is not the place for even a short resume of his bizarre career, but I can thoroughly recommend Dave Thompson’s book ‘The Avant-garde Woodstock’ for a full exploration of what Harvey was about to unleash.

We were invited to visit Harvey at his home in Ingatestone, Essex, where Annea Lockwood had planted their garden with a series of half-buried pianos. He was, he told us, in the final stages of organising a massive, two-week festival of avant-garde music to be based at the Roundhouse in Camden, and to be called the International Carnival of Experimental Sound 1972, otherwise known as ICES. The ebullient and charismatic Harvey invited us to take part, and we naturally jumped at the chance. We wouldn’t be paid, but would get free passes to all events. The only drawback was that the Festival was to due start in a couple of weeks, and the program had already gone to the printers, so we would need to publicise our own shows. However, Harvey agreed that we could make an on-stage announcement after one of the major Roundhouse concerts.

We thought that we had better take the opportunity to make a bit of a splash with our announcement, so we made another visit to the invaluable Laurence Corner and hired an impressive silver space suit, complete with helmet. Our plan was that Max and I would come on stage, me in my space suit brandishing a loudly ticking Geiger counter with which I would sweep the audience, while Maxwell in his white-coated mad scientist persona would announce our forthcoming shows and explain that our music was mildly radioactive and needed to be tested as a precaution.

However, on the designated day, it appears that Harvey had omitted to tell stage management that FART were due to make an announcement after the evening show. On the other hand, we had also omitted to tell Harvey about the ‘art action’ we were planning. I forget which performance it was that we had been told we could come on after, but as we waited in the wings, I was hot and disoriented, finding it difficult to breathe in my steamed-up goldfish-bowl helmet.

As soon as the applause had died down and the musicians, whoever they were, had departed, Max guided me onto the massive Roundhouse stage and I began my Geiger counter nonsense. However, Max had barely started to announce our gigs before we were both jumped on by two burly security men, who, seeing what they perceived as an unauthorised stage invasion, seized us and dragged us bodily from the platform. Cocooned uncomfortably in my cumbersome costume, I had no idea what was going on, but I could hear Maxwell protesting loudly as we were forcibly ejected through a rear door of the building.

The Roundhouse was built in the Victorian age as a repair shop for steam locomotives and was, at the time, still surrounded to the rear by derelict railway sidings. We stumbled around wretchedly in the dark for some considerable time until we found a fence we could climb over into the relative normality of Chalk Farm Road.

Our gigs themselves went well and were held at ‘The Warehouse at The General Store’, a spacious venue directly opposite the Roundhouse. Prior to this, Max and I stood outside the main venue for hours leafleting those leaving the concerts with details of our own shows, which ended up being quite well attended. I remember giving a flyer to John Cage, but I don’t think he turned up.

We also took full advantage of our ICES free passes and saw a lot of strange and inspiring acts. On one occasion I found myself seated next to a young guy who was bopping about in his seat, apparently really digging the honks and squeaks going on onstage.

“Hey, you really like this, don’t you”, I said.

“Yeah, it’s far out.” His voice was a bit slurred, and I assumed he was stoned, like the majority of the audience.

“It’s even more fun to do it”, I said.

“Wish I could, man.”

“Well I’m going to be performing tomorrow, and I can’t play a note.”

“’Fraid I couldn’t though.”

“Why not?”

“I’ve got Cerebral Palsy…”

19.02.20

THE FREE ART RESEARCH TRIO – PART 4

Our most memorable gig came through contacts with the Jazz Centre Society, based at the time, as I recall, in Covent Garden. An old school-friend of ours, Dr David Mitchell, an accomplished jazz saxophonist, was an active member, and when a benefit gig for the Society was announced to be held at the legendary Ronnie Scott’s Club in Frith Street, Soho. We managed to wangle ourselves onto the bill. At that time Ronnie Scott’s Club had an upstairs venue where lesser bands and rock groups performed, but this gig was to happen downstairs, in the Jazz Club proper.

I cannot exaggerate the thrill of actually playing on the same stage, with its strange, undulating plaster rear wall, on which we had seen so many superhuman Gods of Jazz perform. This was Holy Ground to us, and of course in the normal course of events we would never have got within a million miles of performing there.

For the event, the Trio were augmented by David Mitchell on Saxophone, who as a busy hospital doctor, already had his own white coat. I can’t recall whether he partook of our double-tracking facilities or just blew over the top of our stuff, but in any event, it all went down as well as our other gigs. (One advantage of playing Free Music is that one cannot actually make mistakes as such, as there are no right or wrong notes.) I recall the audience enjoyed me ‘playing’ a length of timber by going at it with a saw, the noise splendidly amplified by our trusty throat-microphones. The evening was one of the musical highlights of my life.

Amazingly, both the three minute tape-loop cassettes still survive from our final gig, but I have never considered playing them, as they would be missing the essential ‘third layer’ of live performance that went on top.

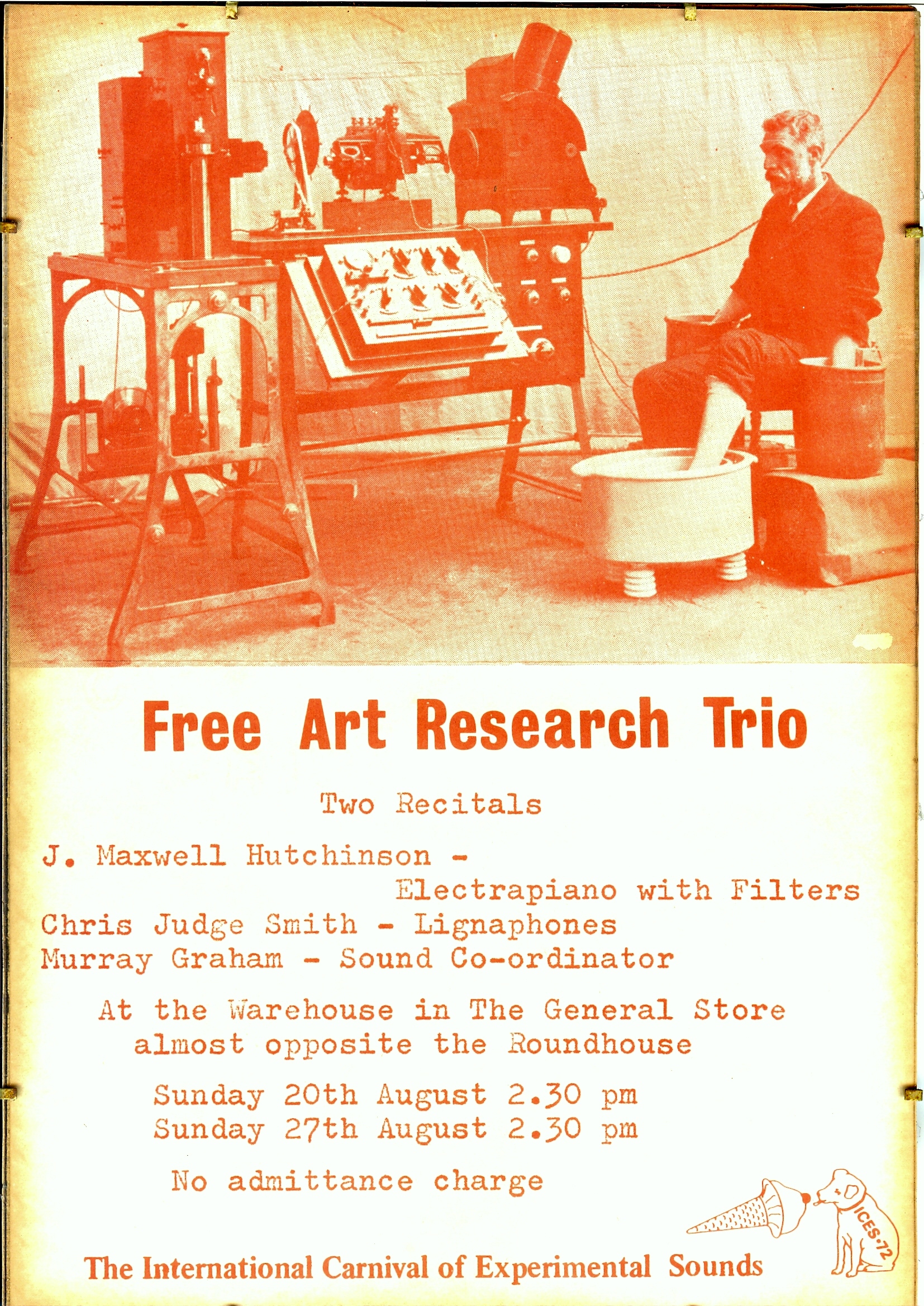

The only photo that survives of the band was taken that night, and can be seen in my Gallery (1972), and here is one of our posters:-